In the world of Project Finance, there are two fundamental rules:

Rule No. 1: Start from Scratch.

This means creating a new project company, a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), with a zero balance sheet. As the project progresses through its development and construction phases, it must eventually become self-sustainable, meeting all obligations using the cash it generates once it reaches the Commercial Operation Date (COD).

Rule No. 2: It’s a Multi-Player Game.

Engagement with various stakeholders is crucial. This includes contractors, co-developers, sponsors, and, most importantly, lenders. Raising debt is essential for project finance, as it adds value beyond equity alone.

Given this setup, you must convince yourself and all stakeholders that the project is sustainable and that all risks, especially during construction, are mitigated. Here are some common mitigation measures during construction:

- Contingency Provision: Allocating extra budget for unforeseen costs and challenges.

- Insurance: Securing comprehensive policies to cover potential risks, such as damage, theft, and liability.

- Liquidated Damages: Imposing penalties for delays or contractual breaches to compensate for potential losses.

- Contingent Facilities: Arranging for additional funding or resources if primary ones fall short.

- Standby Facilities: Backup facilities or financial instruments to ensure continuity in case of unexpected events.

In this post, I’ll focus on the issues around funded contingency provision during construction.

Funded Contingency in the Construction Budget

Anyone who has ever put a budget together knows that you define your base cost estimates and then add another cost item within your budget, which you can call contingency for unexpected events.

The definition is quite clear. However, there are still some questions that can be discussed regarding contingency provision in the construction budget.

Question 1: How do I estimate the contingency required in the construction budget?

It depends. I’m not too fond of this answer. It reminds me of presidential debates where most answers are ambiguous and depend on something.

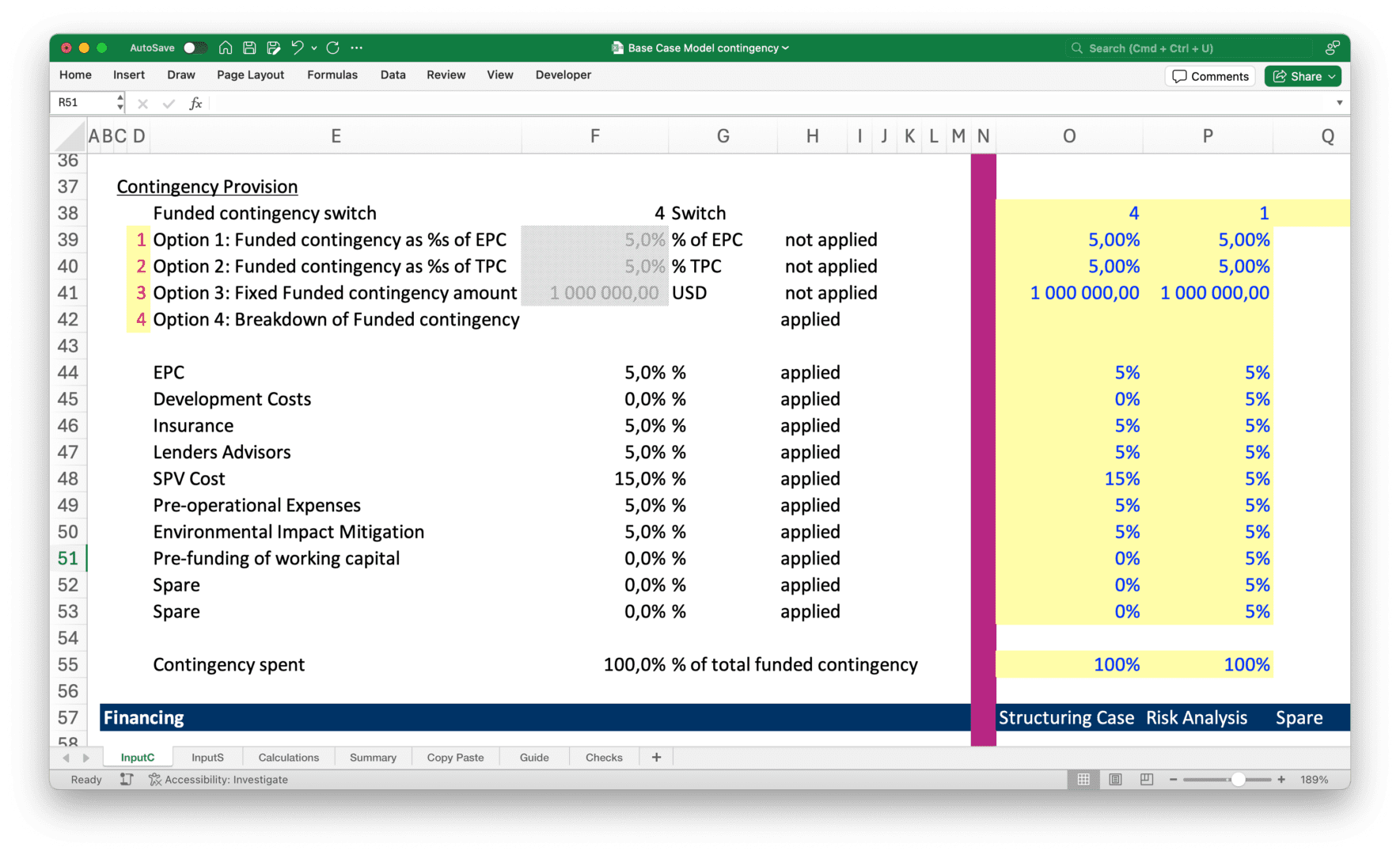

It depends because it’s based on the riskiness of the project. Usually, the contingency is estimated as a fixed percentage of the major cost item in the budget. This is mainly the EPC in infrastructure projects, but it can also be estimated as a percentage of total project cost. This includes contingency on base costs, which typically cover EPC, SPV cost, O&M mobilization, advisory fees (technical, fiscal, legal, financial, environmental, etc.), and any other CAPEX, plus the financing cost (interest during construction, fees, etc.).

Defining the contingency provision for each cost item in the construction budget might also be appropriate. This flexibility is helpful, but be sure not to embed the contingency within each cost item. Instead, reflect it as a separate item in the budget.

Question 2: In which project document can I find the contingency amount?

The technical report. Developers must conduct many studies in a project finance deal, mainly through external consultants. One critical study is the technical study. The project’s sponsor’s technical advisors will compile a detailed report discussing the technical aspects, including reviewing cost items and providing their input on how much should be allocated for contingency.

Developers then compile all documents required in the lender’s checklist and send the reports and a financial model to lenders. This model is aligned with the studies, reports, and legal documents. The lenders will, in turn, hire external consultants to produce their reports reflecting the lender’s point of view. There might be divergences between what the sponsors’ technical advisors estimate as required contingency and what the lenders require. The contingency amount included and funded in the construction budget can still be subject to negotiation. Eventually, what is agreed upon by lenders will be used in the model to size the debt.

For example, let’s say lenders require 5% of EPC to be included in a solar power project. Sponsors may be more optimistic and think they only need 2.5% of the funded contingency, but they agree to use 5% in the lender’s base case. Now, sponsors will use 5% of the construction budget but will look at an upside case where they don’t spend the fully funded contingency.

Question 3: What happens if the project is completed without spending the full funded contingency? Who receives the unspent funded contingency in the project account at the construction end?

First of all, statistically, this rarely happens. I recommend the project management book titled How Big Things Get Done by Bent Flyvbjerg. Unfortunately, you’ll see that the reality is quite the opposite, most projects face cost overruns that go beyond the funded contingency provision.Treating the unspent funded contingency depends on how it is handled in the contracts. I will tell you two cases that I have come across.

Case 1: If the tariff is negotiated on an open-book basis and is set by the financial model, then the concessioner might negotiate the purchase agreement so that the unspent funded contingency (or at least a percentage) goes towards reducing the tariff. This means they ask for another rerun of the financial model once construction is completed and get a new tariff that reflects the unspent contingency. I have seen and modeled this in a power project.

Case 2: Lenders allow the unspent contingency to pass through the cash flow waterfall and be distributed as dividends. If there is a cash sweep mechanism, then a chunk of that will go toward repaying debt tranches.

Question 4: What about the payment schedule for the funded contingency?

If the duration of construction is long, how we assume that the funded contingency is spent throughout the construction phase can significantly impact the project. For instance, if you have a hydro project that takes three years to build, then it makes a difference whether you assume that you will draw down on the full contingency in the first month of construction, the last month, or spread it throughout the construction phase.

But if you are dealing with a solar project that takes 6 to 12 months to build, then how you assume you will draw down on the contingency may have little impact on the total project cost.

In practice, I typically do the following:

Case 1: As I said in my answer to question 1, I sometimes like to have the flexibility to define a different contingency provision for different cost items in the budget. This way, once I size the amount of contingency included in each cost item, I spread them throughout the construction phase using the same payment schedule as the base cost items.

Case 2: I use the payment curve of the highest cost item in the construction budget—typically the EPC—and spread the sized funded contingency amount over the construction period, mimicking the EPC payment curve.

Case 3: Simply spreading the contingency equally throughout the construction.

Question 5: How do we model contingency post-construction when we include actuals?

This should be the subject of another blog post. It is one of the modeling cases that I find both challenging and exciting.